Javier Téllez and Rahul Gudipudi in Conversation

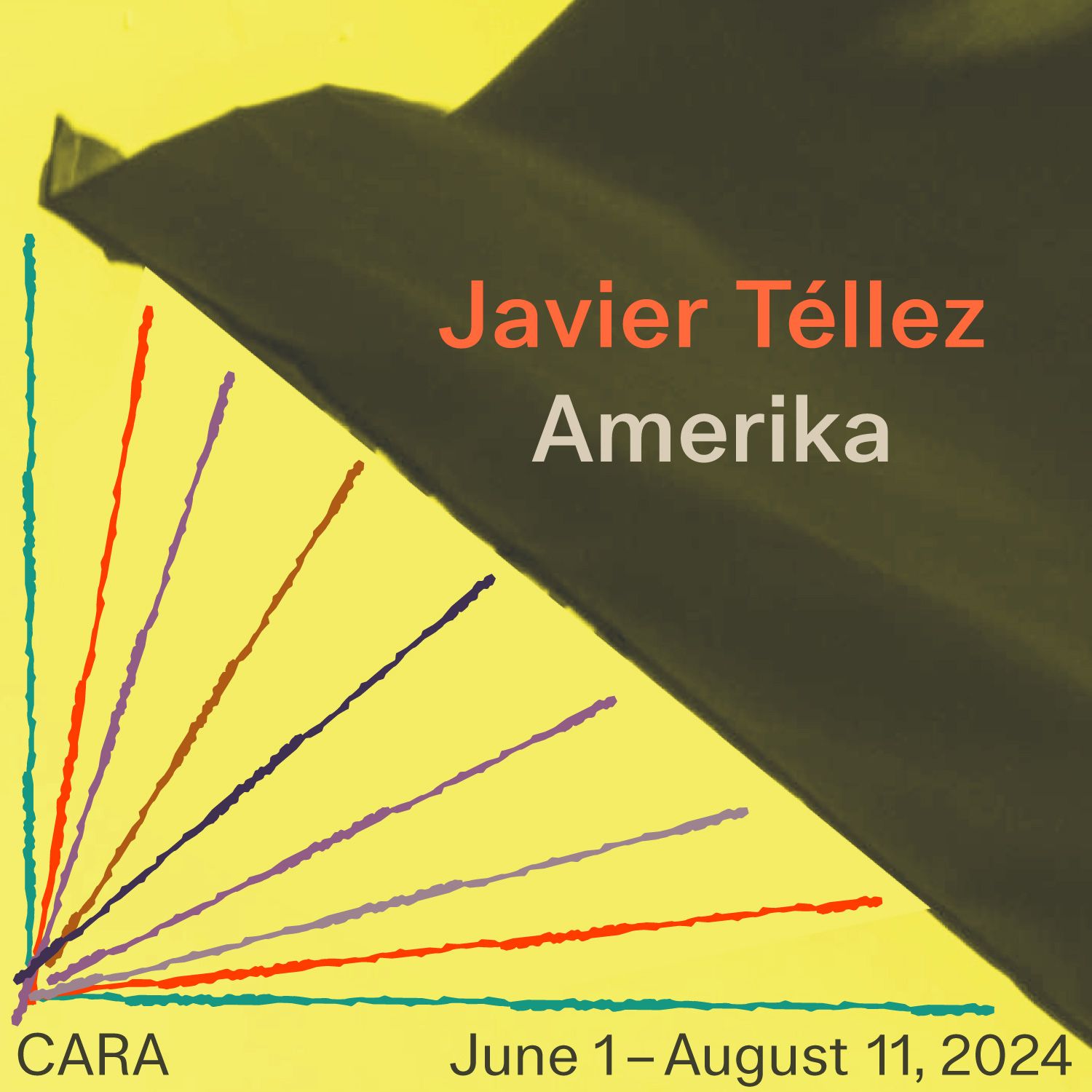

Transcript edited from a conversation on the occasion of the exhibition Javier Téllez: Amerika, June 1–August 11, 2024.

Una versión en español del texto está disponible aquí.

This transcript is edited from a public conversation between artist and filmmaker Javier Téllez and CARA’s Senior Curator Rahul Gudipudi, which took place on June 20, 2024, at CARA, on the occasion of Javier Téllez's exhibition Amerika.

Rahul Gudipudi

Javier, I wanted to start off our conversation thinking about how your practice, at its core, is really a rigorous study of social archetypes and of the production of the image. Perhaps, to begin with, we could talk a little bit about your personal collecting practice, which also informs Cine Capitol. What prompted this rigorous obsession with the image and what it holds?

Javier Téllez

We can talk about multiple obsessions rather than one obsession. Collecting is an important practice; we are all collecting in one way or another: collecting images, collecting smells, collecting tastes, collecting stories, collecting things, and of course, collecting memories as well. I was lucky enough to grow up in a family of collectors: my grandfather was an art historian, so he had a very large library. My father also had a very large library, the largest in the state, whether private or public, with over thirty thousand books. So, I grew up in this library, where there was a large constellation composed of text and images. I have been informed by this constellation since my childhood. In a way, I've been reproducing myself in my own house as well: it's become like a satellite or another constellation of this larger constellation. Over more than thirty years living in New York, I have built a personal library of nearly ten thousand books, a large selection of Latin music records, and a collection of 16mm films, which I screen regularly at a microcinema I started in my house.

My maternal grandfather owned one of the first movie theaters in Venezuela, Cine Capitol, which was also a sort of archive of moving images. For me, any image is a moving image, even if it is a static image. A Bernini sculpture, for instance, could become a moving image because it always triggers a before and after in the imagination of the beholder.

RG

Absolutely, the work is perhaps as much about collecting this history as it is about the misrepresentations present within these images. You categorize them in certain apparent ways, but there are also underlying cross-associations that inform or reference some of the works. There is an invitation to classify or revisit these associations, the multiple obsessions we see within each of the panels. There are hidden coincidences and recursivity that emerge as a through line through your practice. I wonder if you could speak about that?

JT

I tend to classify, but it's also by classifying things that you realize that classification itself is impossible. It's more about rethinking the idea of montage: instead of grouping several images together like a collage, I group images that can respond to a subject, because they are either associated with my biography or with my work. There are a thousand subjects that make up the series of Cine Capitol. I named the work after my grandfather’s movie theater because it is a very cinematic project, in the sense that it refers to pre-cinematic toys, which often included circular images, like the thaumatrope, the phenakistoscope, and the magic lanterns.

RG

Can you expand on that? There are several occasions where you actually juxtapose the circular image against the rectangular four by three, or a square or 16mm aspect. In Games are Forbidden in the Labyrinth, for instance, you pair circular images against the square images. There is also a relationship to this idea of the hole, the cave, drawing from Plato and Orcus. This is, again, a through line that, of course, is present in the theater, but also within these atlas categories and in the individual images, because often you also find an image within an image, as you said, or an image will look like a film within a film.

JT

They are circular because I see them as samples—a reference to the image, not the actual image. It's a cut-out of the image, like seeing the image under a microscope. There’s the idea of omission, excision, what is left out of [Leon Battista] Alberti’s window. It's also easier to group them together as circles than as squares, like a constellation of planets.

RG

And you don’t just refer to the representation of these associations, but also often the misrepresentations that are very present within the ways in which they are classified. And those misrepresentations show up, as do archetypes, within quite a few of the works—in the characters, the archetypes, whether they are marionettes or wax figures, or the figure of the dictator, for instance, which informs the film AMERIKA.

JT

It's a very carnivalesque principle. In the carnival, everybody becomes a sort of marionette; in a masquerade, we are the representation of a character, not the actual character… The puppet and the puppeteer. It’s a bit like Borges, who said in a poem: “God moves the player, and he, the piece.” But who is the God behind God who begets the plot? It's always a question of who is behind the puppeteer. How is our own identity defined by how others perceive us? Who are we beyond the social constructs?

RG

Well, speaking of the puppeteer who moves the puppet, I'm thinking through your very early relationship to being introduced to mental health as a subject, and questions around psychiatry and psychology. Can you talk about how your childhood informed your practice?

JT

Both of my parents were psychiatrists. I grew up in a very special house. My father held private consultations in the house in addition to his work at the hospital. He was an intellectual, and as I mentioned before, had an incredible library. It was a big house, but with very little space for us in the interior because there were books everywhere, so we often played in his consultation room. We were really in daily contact with people diagnosed with mental illness. That shaped me and my brothers: my brother is a psychiatrist and I often work with people with mental illness. I think that people’s conception or stigmatization of those who are mentally ill starts at an early age. In our case, it was obvious for us from childhood that notions of normalcy and pathology were constructed.

There's a beautiful book by Emmanuelle Guattari, Félix Guattari’s daughter, called I, Asylum. She had a very similar experience, growing up with her father in La Borde, the psychiatric clinic where he worked. I think it's always great to expand your mind and not be reduced to social constraints.

I feel blessed to have grown up like this. As an artist using film as my main medium, I eventually approached people diagnosed with mental illness to work and collaborate with me in my projects. At first, I started out by making pieces about them, but realized that I was not able to do these pieces on my own: I needed to start building relationships and make the pieces together.

RG

How have these relationships changed over time, over the course of different projects and throughout your practice—through different subjectivities, the learnings your works bring over time, or the practical conditions of each piece? I'm curious if you've revisited certain strategies, or how you invite or engage with your collaborators and the modes in which those collaborations materialize?

JT

Each case is different because I encounter different people. But there is a lot of repetition, because this is something that, as artists, we cannot avoid. Our obsessions are always present. It's a negotiation between my own subjectivity and that of others. It’s my work, not a purely collective work, but it is made with the help of others. The work is built in the interface of that dialogue.

For me, cinema itself is a tool for that dialogue—a tool to talk to the other, to learn how to represent the other, which is a question that has always been on my mind as an artist. I grew up as a Catholic, and for most Catholic artists, the question of creating an image is a question of how to represent the other; this was one of the main discussions in the Council of Trent [in the sixteenth century], and was later was expanded upon Baroque painters like Caravaggio, Ribera, Velázquez, and others. These painters looked at those who had been excluded from representation—the beggars, the criminals, the prostitutes—and had them pose as saints, apostles, and virgins. It is a form of realism—to contest an idealistic, classic view of the other, and to attempt to represent the other as they are, which is, of course, impossible.

RG

You’ve spoken elsewhere about how Luis Buñuel’s work engaging with nonprofessional actors has also informed your desire to really enable these possibilities when engaging with nonprofessional actors.

JT

Luis Buñuel is always relevant. Another figure who is essential, of course, is Roberto Rossellini. Rossellini is the one who left the studios and brought the camera out to the streets. It's an important rupture. He was not the only one, but with Roma città aperta [Rome, Open City, 1945], he opened the field for people like Jean Rouch and Pier Paolo Pasolini. He really initiated a way to represent the other in film that is in-between documentary and fiction, which is the area in which I like to situate myself.

RG

You’ve worked with the visually impaired, with migrant communities or people seeking refuge, and with psychiatric patients, but one thing that I find also present when looking through your works is how these identities are merged, and how all of these identities and their representations are a reflection on society in a certain way. Through these reenactments of the various literary or cinematic references that you reinterpret, new possibilities emerge which are situated in the past, and yet urgent and contemporary, like in AMERIKA, for instance.

It reminds me of the relationship between the Wayfarer and the Fool and your references to Bosch. You’ve played with the idea of the Fool, and when I say play, I mean verbally, linguistically, with the notion of the fool and the folly, but also in relationship to the wayfarer. I'm thinking specifically about One Flew Over the Void (2005), but also thinking about your 2004 work La Batalla de México (Hospital Fray Bernardino Alvarez) with the Zapatistas, which was one of the earliest works that, again, engaged with psychiatric patients. Whether it's migrant rights or actors engaging in social commentary, you bring in these intersections that are very current.

JT

I think it has to do with the carnivalesque aspects of my work… Of course, I made a choice to work with disenfranchised people, people who are segregated, because I feel they need to be brought in. I love Paul Klee’s definition of an artist as someone who makes things visible. It is important to give visibility to populations that are otherwise cast out. It would be so irresponsible to be in a world that only has to do with one’s own subjectivity. It's about building bridges, bridges between people.

RG

This is where the characters present in the films that you revisit play an important role. Maybe we could look at the characters of The Tramp (1915) and The Immigrant (1917) as a way to introduce the film AMERIKA, and think through why Chaplin is a figure you've been thinking about for some time, and of course, in relation to subject for this particular film.

JT

I've always loved Chaplin. I also always loved Buster Keaton too, but I often encountered the appreciation toward these comedians as being posed through the question: “Chaplin or Keaton?” Just like when people ask “The Beatles or The Rolling Stones?” It’s a silly question.

I think people privilege Buster Keaton too much over Chaplin. Even Buñuel would say that Chaplin’s humor was too intellectual and not for children or farmers. However, my son loved Chaplin when he was a child, and the people who worked with me on AMERIKA loved Chaplin from the beginning. They didn't know Chaplin until I introduced him to them. You don’t need a higher education to understand Chaplin.

For me it is important to understand film as the medium of the twentieth century par excellence. Godard said the history of the twentieth century is the history of cinema. It is necessary to rescue these films from potential oblivion, to re-interpret them. Who is better than Chaplin to represent the history of film as a medium? What does Chaplin mean today? And who is the best person to interpret Chaplin today? That is where I thought of the Venezuelan immigrants. Being Venezuelan and a migrant myself, I was drawn to the subject of the exodus of over nine million Venezuelans, who left their country in the last decade due to the humanitarian crisis there. I had already addressed the subject in 2019 in a video installation titled Los Caminantes, made in collaboration with Venezuelan migrants in Peru, for the Aichi Triennale in Japan. But it was essential for me to address this topic in New York, the city where I live.

RG

Can you share more about the process behind the making of this film [AMERIKA] in particular and the collaboration, and how you began to think about how you would engage with the asylum-seeking community and the everyday process of how the collaboration played out?

JT

Some people ask me about these workshops, but I prefer to call them meetings because the word “workshop” sounds too serious. But in fact, it’s not that complicated. We meet, we introduce ourselves and get to know each other. Then I invite them to consider the possibility of making a film together. This is how every project starts. I usually begin with people who are in mental institutions or shelters, in what Erwin Goffman would call “total institutions.” I approach these institutions because the people are already there, it’s a practical thing—they're all there, I introduce myself, and I let them decide whether they want to work with me or not. I usually start with a larger group of people, then they meet me and say, "Well, he's not from Hollywood." [laughs] And they start “outcasting” me [laughs].

In the end, I end up with a very small group of people who want to stick around. I start meeting with this group, and it usually goes very fast; I accelerate the process before they completely ditch me. If I stayed too long, we would never do a film, they’d say, “It's time to go” [laughs].

I came up with the idea of doing Chaplin, so I approached some people who work in the shelters, to introduce me to potential collaborators. I would say, "I want to make this film" and they would ask "What is the film going to be about?" When I showed them Chaplin films they agreed.

During our meetings we watched many Chaplin films, shorts and features. They became really addicted! I tried to introduce other films, but they would say "No, no, we want Chaplin" [laughs].

RG

Did you show any of your work?

JT

They saw some. They would always say, "Ours is going to be better." [laughs]

The process was basically this: I showed them 16mm copies of Chaplin films, we improvised a screen with paper; then we selected some scenes, watched them again and again, and tried to decompose these scenes to end up with a script that tied these scenes to stories they wanted to bring in. For instance, they wanted to bring in the idea of the vulture instead of the chicken [from Chaplin's film Gold Rush], because they had a horrible experience while crossing the Darién Gap where they had to eat vultures out of hunger.

One important part of my projects is always location, because the location becomes another kind of conversation piece. The film classics are a material to be used in the same way that you use a blackboard: you use Chaplin to write on top of it, to erase and write on top of it. But the location is also very important because it defines the narrative. So, in the end, we chose Fort Totten, a fort that dates from the Civil War, and it was an amazing location for the film.

The final scene came about because in our meetings we had these long tables where we always took a break to eat between scenes, and we often sat all facing the screen to keep watching the films while eating. Their position was just like the Last Supper, so we decided to use it in the film.

RG

You make an active decision to shoot on film, which does so many things in terms of creating that moment of reality that you spoke about by allowing for what's been captured to become the work, and for it to not be over-rehearsed, overshot, or overproduced. It's a difficult but also a beautiful choice... I mean difficult, also practically, in terms of higher production costs, the limited material you have to work with when you're at the editing table.

JT

It certainly is a choice, because I do believe that film itself has a different relationship to reality than digital media. Maybe I'm old, what can I say? [laughs] I think film is fascinating because it is like the “Veronica” showing the face of Jesus—it is a direct print of reality. But of course, it also gets filtered because it's edited digitally, so it's not shown in film anymore. I've done projects that are shown in film only, but it becomes too complicated, even though I enjoy it. I think we should shoot in film until it disappears because it's now on the verge of disappearing, and if you're making something with Chaplin, it makes sense to shoot in film.

RG

There's again that gesture of rescuing from oblivion and a relationship to craft.

I have one last question in relation to collaborative practices and the way that they emerged through your practice in particular with “non-human actors”, living and not living. I'm thinking about the elephant Buelah [referencing Téllez's work Letter on the Blind for the Use of Those Who See, 2017]. I'm also thinking about the number of times you visit taxidermy: in this exhibition you're working with taxidermy toads, but you've also worked with a taxidermy fox, with a taxidermy lion, with a rhinoceros. It’s an active collaboration with a being, an entity....

JT

This has a relation, again, with cinema and the history of cinema. Perhaps the most beautiful essay by André Bazin, “The Virtues and Limitations of Montage,”1 precisely refers to the encounter between animals and humans, because it's not only the animals; there’s also always a human next to them in my work. Bazin writes about a scene in The Circus, where you see Chaplin and the lion together in a cage. That’s a memorable moment when you have these two elements in the same shot, and this is precisely what Bazin celebrated in his essay. It was not pure montage, like the sort of montage that [Sergei] Eisenstein defended, it was real according to Bazin. The encounter between a human and an animal is perhaps one of the most cinematic events ever.

RG

And to blur that line between the human and the animal in certain ways... which is reflected in the protest signs, where one of the protesters rejects the characterization of immigrants as animals, this reference toward the other as the nonhuman and the rejection of that rendering by society.

JT

Becoming animal, a subject dear to Deleuze and Guattari… you can see this in AMERIKA in the vulture dream. He becomes a vulture in the eyes of the other, a scene that quotes Chaplin, of course.

I was reading an account of Chaplin during the filming of Gold Rush, where they said he completely transformed into a chicken during the scene. Even when he wasn’t filming, he still acted as a chicken. They said he was acting like a chicken. [laughs]

The actual dynamics of Chaplin’s production were very unusual. He didn’t work with a script, he just continuously thought of gags, and there were days when there was no filming at all while he was just getting inspired or thinking about new gags.

RG

The last scene [from the Chaplin clips played previously] also reminds me of something that's very present in The Great Dictator and in several of your films: the double character, where the same individual plays two roles.

The Great Dictator lends itself to the story of your film in a beautiful way. But, in some of your older works, there's always this gesture of the actors watching the film and then watching themselves, and the way they are transported by that. It allows, at least for me, for the viewer to be able to imagine themselves both in solidarity with, or sitting amidst the actors in "reality," and it reproduces this idea of the film within a film, within the zone of being. I'm keen to learn more about when you started to consider that gesture.

JT

It has to do with my biography and my experience visiting the carnival in the psychiatric hospital where my father worked at the age of seven or eight years old. We would go there every year during the carnival, and it was really interesting to see patients exchanging their uniforms with the doctors, so that the patients would dress in the doctors’ white coats, while the doctors would wear the patients’ uniforms.

For me, as a kid, it was kind of a revelation, because I knew all the psychiatrists and I knew some of the patients, but to actually see this reversal… What happens when we reverse roles? This question emerged for me from my life experience, before reading Bakhtin or getting interested in Flemish paintings. That question is present for me in all carnivalesque art and literature, this kind of masquerade. It's quite a force. I think it's a liberating force. Some people criticize carnivals, saying they are only reinstituting binary oppositions, but I’m of the mind that the carnival can be a space where conditions can be challenged and reality transformed. So, for me, it's a very essential exercise of freedom to reverse roles.

In my work, my collaborators become actors, but they are also spectators, and they can change roles. In the fictional narrative they can be the victims and they can be the victimizers, because in the end it's all a game. All representation is, in the end, a game. One thing that is important for me is that at the end, it has to be fun in order to succeed. Beyond the aesthetic, it has to be fun for them. So I hope it's always fun [laughs].

RG

We can open it up to questions.

Audience Member 1

I come from a position of naivete, first of all, because I unfortunately didn't get here early enough to see the film... So that's one position of naivete, and the second is not being very aware of the condition of psychiatry and psychology in general within the Venezuelan context. I'm familiar, in passing, with the way in which psychoanalysis is dealt with in Argentina and Brazil, but not at all in Venezuela. So I have a two-part question. One is very factual: How is psychiatry and institutional psychotherapy seen in Venezuela? How is it supported through state systems, through institutions of mental health insurance, these kinds of things?

The second is: Obviously some things [about your practice] I imagine come through observation, through participation, through osmosis, but I'm curious within the group methodologies that you're using, the workshops with the cast, if there are specific tools or methods that you learned or practiced in order to be able to use these workshops in the most generative way? And if so, how did you learn the tools that you use to facilitate these group interactions, beyond that which was given to you by your background?

JT

Yes, great questions. In terms of psychiatry in Venezuela now, it’s not easy to answer that question because there are two different realities: one before Chávez and one after Chávez. The situation of people with mental illnesses in Venezuela is worse than it ever was. Institutions in general, hospitals in general, are not very well attended to by the state. Hospitals have been public for decades now, long before Chávez. Psychiatric institutions run by the state are in really poor condition. The capacity of these institutions is considerably downsized so people with mental illnesses are living on the streets.

Venezuela doesn't have a particular history of anti-psychiatry like the radical practices you find in Brazil, Mexico, and so on. It's been mainly institutional—I mean, real, institutional, psychiatry. It's basically social assistance for people with mental illness. Within that you have very specific doctors and psychiatrists. Many of them came from Europe. That's the case of my father and that's the case of someone like José Solanes , who was actually François Tosquelles’s best friend.. Tosquelles was a Catalan psychiatrist, basically the founder of institutional psychotherapy. His friend José Solanes was actually in Valencia, the city in which I was born, and he worked in the psychiatric hospital with my father.

Regarding my practice with people, as I said, I think there's something that I carry from these experiences with psychiatry. Even if I'm not a professional, not a therapist... I always say that it's more about curing the people who think that they are normal. It's more about curing the viewers, rather than curing the actors. But of course, when I work with people who are not diagnosed with mental illness, but actually have post-traumatic stress since they crossed the Darién [Gap]... I carry some of my experience from my childhood and from growing up next to people with diagnoses. But I don't have any particular methodology other than that. It's basically a cine club. And I do this in my house as well. I turned my house into a small movie theater, a micro cinema. I show only 16mm film to up to ten people, by appointment. That's the maximum capacity of my living room. I project from the kitchen, and I have a large collection of 16mm films, so I have run programs there.

Audience Member 2

I was wondering if you could speak to film and how you understand it. Because what I think is very striking about AMERIKA is that, in some sense, it extolls the structure of narrative cinema, but at the same time, it's a film about a film or a set of films, and also about film in general. Being a film within a film it depicts self-identification while also producing some kind of estrangement. I'm thinking about Brecht. You mentioned film as a quintessentially twentieth-century medium, so I would love to hear more about this.

JT

It’s like a Chinese box–a box inside another box inside another box, which repeats again and again. A journalist was interviewing some of my cast, and he kept using this word which I actually question: "experimental." Experimental cinema, what does that actually mean? You might say, basically, a kind of non-linear narrative film. But, I will also defend this kind of super traditional narrative from the 1001 Nights, for instance–the idea of fables and the storytelling. I would have never convinced my cast to make a Michael Snow Wavelength film. They would have said to me: "What are we doing?" [laughs]. But they identified with this scene that they can actually work together in producing a micro narrative.

Micro stories don’t have to be conclusive. They don’t have to have a beginning, a middle, and an end. But that doesn't mean I'm not reflecting on the apparatus in the way that I, of course, admire in people like the so-called post-structuralist filmmakers, or Ken Jacobs... I'm trying to do something else. I'm trying to do some work with the people in this story. And I think this is quite cinematic. Like in early cinema, for instance, the way Méliès tells stories, which is very poetic. It’s just the idea of how to make essential stories collectively.

Audience Member 3

Did you notice with your actors any epiphanies about how common these humorous tropes are across a long time? Since, the films that you use in the workshops can resemble their present journey. For example, the things that happen in the boat [in The Immigrant], they may also have experienced in life, traveling through the Darién. But at the same time, they saw their conflicts brought to light. In Gold Rush, the scene where there is a struggle over food could resemble things that they experience... Did they appreciate the art of it?

JT

I think the fact that they were all doing it together and they knew they were doing it in a space which is a space of fiction, not a documentary space, was important. They are not talking about their experiences, they are talking about Chaplin. It's a bit like the iceberg image: you have the visible part and the invisible part. They are comfortable in that.

I have high respect for the word epiphany [laughs], but I wouldn't say that it creates an epiphany. But maybe this will be my goal from now on: it should be about epiphanies [laughs]. I hope it creates an epiphany for the viewers more than the actors.

Audience Member 4

Francisco Goldman, a writer and journalist in Central America, told me that he was a "fictional writer" when he was really covering things for The Nation, etc. He said "No, you get your ass over here and you're going to see reality as real fiction."

JT

I mean, I believe in reality [laughs]. I am not saying that reality doesn't exist. But in terms of genres, when you see any film, there's always something documentary in the film. One of my favorite definitions of film, and this helps me to watch any kind of film, is from Man Ray. Man Ray said "It doesn't matter how bad a film is, at least you can rescue two, three seconds of it." He said there are three seconds in any film, no matter how bad it is, that are great. So these three seconds, perhaps, are what is real, and the rest is just fiction. When I see Jack Nicholson acting as Jack Torrance, he is still Jack Nicholson. There's something that is truly documentary in any film and there is also obviously something that is highly fictional in any documentary.

Audience Member 5

You mentioned that the subjects, the individuals who are in the film, are representing their own experiences coming to America. I was thinking about that in relation to how in reality TV, we see people talking about their experiences all the time. What is different about referencing a sort of essential story like Chaplin’s, referencing these archetypes that have existed, that exist outside of individuals’ experiences... Why do you choose to have the people play a different story, as opposed to write their own?

JT

Very, very good question. One of the things is that I'm not working with one single person in the film. So, first of all, it's my own subjectivity. But second, I'm working with a group of people. This group of people, in many cases, haven't met before or met for the project. There are cases where some of them knew each other, but not all. So in a way, to create this excuse to get together, to meet together, to make a film using something that has already existed, allows us to create this multiplicity, where people can project their subjectivities without being actually themselves.

And it is my interest to create something that goes beyond their own personal story; I am interested in the realm of fantasy, in fables and oral stories. I am interested in collective narrations. In the type of work I'm making, I’m not saying, "Okay, let's make a documentary about their life and where they were and where they passed through, where they are now, and where they're going in the future." It's a very complex thing. [laughs] That is really the standard documentary approach. I prefer to have the approach of focusing them [the cast] on creating new images, taking existing images as a point of departure. Which is always the case…one image creates the other. You can never make an image out of nothing.

1 André Bazin, “The Virtues and Limitations of Montage,” in What Is Cinema?, vol. 1, ed. and trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 41–52.